When Cooking Became Entertainment: The Future of K-Food Content

MEDIA & ENTERTAINMENT | INDUSTRY DEEP DIVE

When Cooking Became Entertainment: The Future of K-Food Content

From Julia Child to Chef’s Table, Culinary Class Wars, and Mukbang—How Streaming Turned Local Food Programming into a Global Industry

Food content has evolved over six decades since Julia Child’s television debut in 1963, progressing through four distinct phases: education, entertainment, competition, and social media. However, the true game-changer was the emergence of global streaming platforms led by Netflix.

When Chef’s Table began streaming simultaneously in over 165 countries in 2015, local food programming was fundamentally transformed into global content. South Korea exported its uniquely original format—Mukbang—to the world, ushered in the “Cheftainer” era with Chef & My Fridge, and achieved Netflix’s global No. 1 ranking with Culinary Class Wars, now confirmed through Season 3. The Associated Press reported that the show has transformed South Korea’s entire fine dining market.

In 2025, K-Food+ exports reached a record $13.62 billion, with instant noodles (ramyeon) becoming the first single product category to surpass $1.52 billion. The Korean government has set a target of $21 billion by 2030, positioning K-Food as a strategic industry.

PART 1

60 Years of American Food Content Evolution

1-1. Julia Child: The Big Bang of Food Content

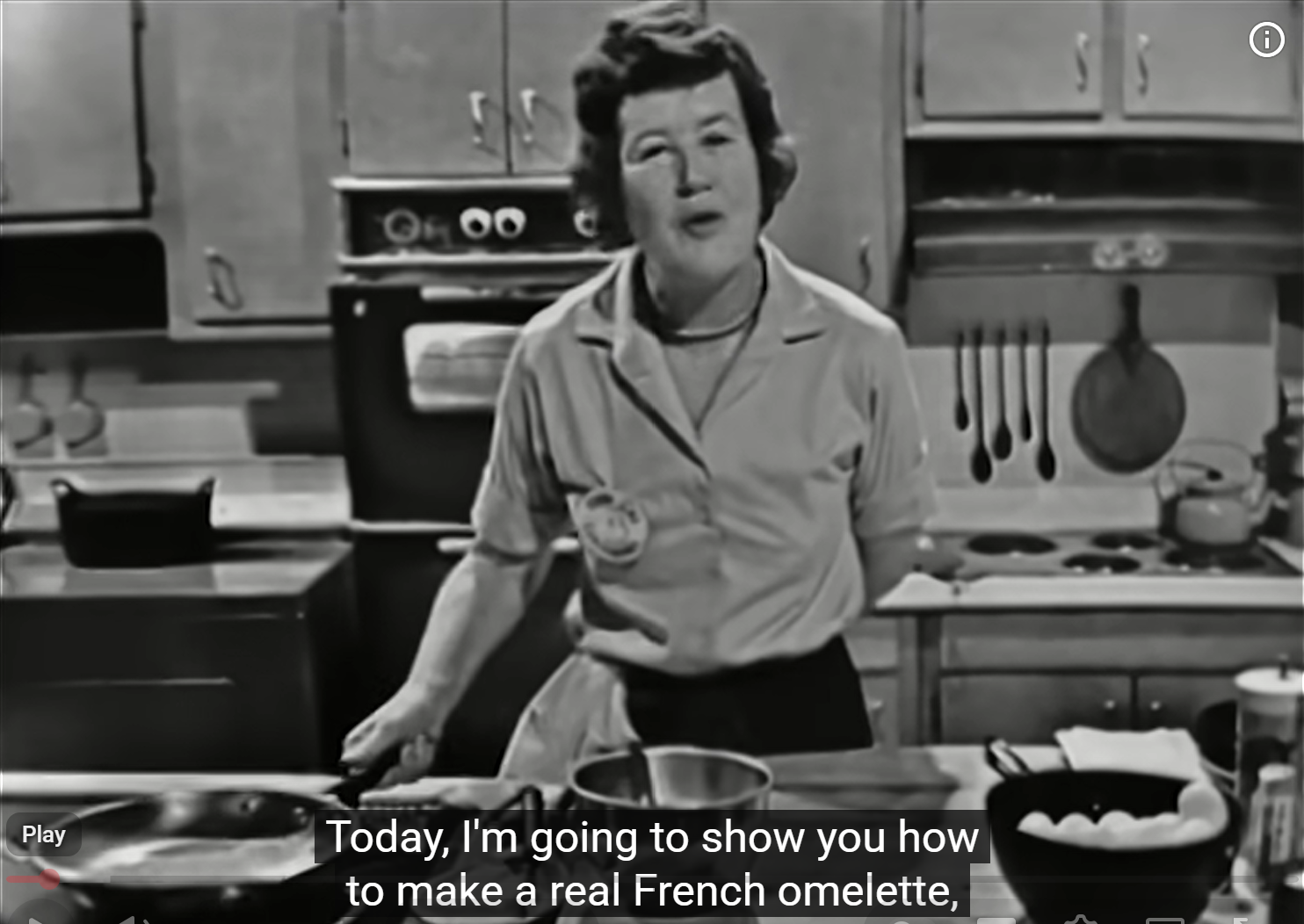

The Wall Street Journal recently highlighted the history of cooking shows gaining recognition as a full-fledged entertainment genre. Julia Child, who appeared on American television in the early 1960s, completely transformed the paradigm of culinary education programming.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N40qglGNRlA

Having formally studied classic French cuisine in Paris, she demystified French cooking for American households during an era when iceberg lettuce and canned mushrooms were the culinary frontier. Her show, The French Chef, aired over 200 episodes and became a catalyst for diversifying American food culture. According to the WSJ, Child’s friend and fellow French-born chef Jacques Pépin recalled that in 1959, the only salad one could find in New York markets was iceberg lettuce.

Julia Child on The French Chef — the show that launched food as television content

Every episode began the same way: “Today I’ll show you how to make a real French omelette.” The word “how-to” was always attached. It was, in essence, a culinary education program.

— WSJ, citing interviews with Jacques Pépin and Emily Contois (Feb. 12, 2026)

1-2. Food Network: From Culinary Education to Food Entertainment

The golden age of American cable TV began in the 1980s, with genre-specific channels for sports, news, children’s programming, and music appearing in rapid succession. A channel dedicated exclusively to food was born amid this wave. TV Food Network (later Food Network), launched in 1993, was an ambitious joint venture between cable operators and media companies, but initially struggled with low ratings and weak advertising revenue.

Early programming consisted mostly of studio-based educational shows where chefs calmly explained recipes. To save on production costs, the schedule was filled with mass-produced instructional formats—essentially a cable version of Julia Child-style public broadcasting cooking programs. But viewers did not stay long for simple “cooking process viewing.” Audience behavior was already shifting toward entertainment, and the channel’s identity was limited to appealing only to “people who like to cook.”

The decisive turning point came in 1996 when Erica Gruen was appointed CEO. She redefined Food Network’s brand positioning from “TV for people who cook” to “TV for everyone who loves to eat”—pivoting from a recipe education channel to a mass entertainment channel celebrating food, chefs, and dining culture.

Emeril Live — the show that transformed Food Network into entertainment television

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bTElHFtI6PQ&list=PL1b0JtKaqoP6uUmLM2Pf9DtH_-GrEjQcD

The program that embodied this new strategy was Emeril Live (1997–2007), hosted by Chef Emeril Lagasse. From the start, this show was different. Gruen and the production team designed it not as a simple cooking demonstration but as a talk show/variety format with live audiences and a house band, staging cooking as a performing art. Emeril’s signature catchphrase “Bam!” combined with audience reactions, music, and humor established Food Network as a channel for “watching and enjoying food shows” rather than “following recipes at home.”

The results were a resounding success. During Gruen’s tenure (1996–1998), Food Network multiplied its ratings and ad revenue several times over, becoming one of the fastest-growing cable channels. Subscriber counts expanded from tens of millions of households in the mid-1990s to around 50 million by the early 2000s, establishing the precedent that a food-only channel could transcend its niche to become mainstream entertainment.

1-3. Competition, Travel, and Social Media: The Third Wave of Food Content

According to the Wall Street Journal, food content subsequently expanded in three directions.

Iron Chef America — food competition as spectator sport

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M7uhDrPnMzo&list=PLZ6W9OsUauMx82XUXhjUf4lUowGCIy72H

First was the competition format. The success of Japan’s Iron Chef reinterpreted the chef as a star athlete and the kitchen as an arena, leading to Iron Chef America (2005–). With time limits, secret ingredients, sports-style commentary, and camera work, this show turned cooking into “a contest with winners and losers,” expanding food content beyond educational programming into competitive reality entertainment with drama, characters, and narrative arcs.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iOFuHGy00yo

Second was the fusion of food and travel. Chef Anthony Bourdain, through CNN’s Parts Unknown, used food as “a doorway into culture”—a portal for understanding other people’s lives and societies. He tasted everything from street food to fine dining across cities and countries, connecting each plate to politics, history, class, and immigration. In this format, food was no longer a vehicle for learning recipes but a narrative device for drawing out local voices and memories, and a tool for documentary journalism.

In Korea, this food-travel hybrid format is equally familiar. tvN’s Three Meals a Day, Youn’s Kitchen, and Unexpected Business, as well as TV Chosun’s Heo Young-man’s Food Journey, use specific locations as backdrops, revealing local lives and culture through neighborhood restaurants, traditional markets, and local ingredients.

Third was the rise of social media. With smartphones and short-form platforms, cooking ceased to be a genre scheduled by broadcasters and became everyday content anyone could film and upload. In 2022, Ali Hooke’s “Tin Fish Date Night” series went viral on TikTok, repositioning canned seafood paired with wine as an “affordable luxury” and triggering explosive reactions, especially among Gen Z.

The “Tin Fish Date Night” trend on TikTok — social media reshaping food categories

https://www.youtube.com/shorts/7Yrva7yf_g8

This trend catalyzed a surge in U.S. canned seafood market sales. The TikTok “Tin Fish Date Night” craze repositioned tinned fish from budget convenience food to a “reasonable luxury” enjoyed with wine and cheese, transforming the category’s image. As a result, tinned fish shelf space expanded across major U.S. retail channels, and premium imported brands gained new distribution.

According to the WSJ, canned seafood category sales in 2023 recorded double-digit growth compared to 2021, marking one of the rare cases of structural growth among processed food categories that had stagnated since the pandemic. This represents a classic “vertical viral” phenomenon—where social media memes and individual creator content combined to lift demand across an entire category.

Thus, food content has followed the trajectory of “education → entertainment → competition → social media viral” over the past 60 years, expanding its audience and creating new revenue models at each stage.

However, until the peak of the Food Network era, most of this trajectory was fundamentally a “domestic U.S.” phenomenon—built around cable TV subscribers, American advertisers, and American production systems. Apart from format exports and remakes in select countries, the influence was relatively confined to North America and English-speaking markets.

What fundamentally shattered these geographic and platform limitations was the emergence of global streaming platforms.

Netflix’s “Crazy Delicious” (Michelin Madness) — streaming bringing local food stories to global audiences

These platforms also opened global direct-distribution channels for non-American creators. Cases of local food content from Korea, Japan, Southeast Asia, and Latin America breaking through domestic cable limitations to reach global main feeds are increasing, with food programming and streaming serving as critical infrastructure for K-Food’s global expansion.

According to industry data, agri-food exports surpassed $10 billion for the first time in 2024, with 2025 estimates at approximately $13.6 billion. K-Food is assessed as one of the few structurally growing sectors in Korean exports. Key products—ramyeon, kimchi, seaweed, snacks, and sauces—show near-double-digit annual export growth, with ramyeon recording mid-20% growth in 2024–2025 to become a market well exceeding $1 billion.

PART 2

The Streaming Revolution: How Local Food Programs Went Global

2-1. Chef’s Table: How Simultaneous Streaming in 165 Countries Changed the Game

Netflix’s Chef’s Table, debuting in 2015, is widely regarded as a watershed moment that fundamentally changed the paradigm of food content. While existing TV cooking shows focused on recipes and cooking processes, this series devoted each episode to a single chef, exploring their life, philosophy, and restaurant context through cinematic visuals and music, establishing a new grammar for food documentaries.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B8OBZaabEOE

In a 10th anniversary interview with Fine Dining Lovers, creator David Gelb reflected: “When we started, we were only available in the U.S., but now we stream in over 165 countries. That is revolutionary.”

This is where the decisive difference from the cable-era Food Network becomes clear. While Food Network was a “domestic” channel that grew around U.S. cable subscribers, Netflix was designed from launch as a streaming platform premised on simultaneous global release. The same episodes reaching viewers in Seoul, New York, Mexico City, and Shanghai simultaneously created a structure where a restaurant in any city could become a “global pilgrimage site” in a matter of days.

Chef’s Table — transforming local chefs into global brands across 165 countries

The impact felt by chefs has been profound. American chef Nancy Silverton, reflecting on the series’ 10th anniversary, shared: “People come up to me crying and hugging me. They tell me they’ve watched my episode multiple times.” She described how TV exposure had transcended mere name recognition to create emotional fandom.

Barbecue pitmaster Rodney Scott similarly noted: “My restaurant became the center of the global barbecue conversation,” describing how a local shop became a global reference point for barbecue discourse. This suggests that streaming exposure has created a structure where visibility translates directly into global visits, reservations, and collaboration requests.

Rodney Scott — from local pitmaster to global barbecue icon through streaming

From a business and brand perspective, the implications are equally significant. Fast Company noted in an analysis piece that Netflix “treated chefs not simply as cooks but as artists, and with an international perspective, turned restaurants into travel destinations and chefs into global brands.” Chefs who appeared on Chef’s Table reported tangible changes post-broadcast: months-long reservation waitlists, increased offers for overseas pop-ups, book tours, brand collaborations, and expanded tourism demand in their restaurant’s city.

Netflix also experimented with extending this global fandom into offline experiences, most notably through the “Netflix Bites” project—a pop-up restaurant in LA’s Short Stories Hotel in the summer of 2023 that brought together chefs and mixologists from Chef’s Table, Iron Chef: Quest for an Iron Legend, Is It Cake?, and Drink Masters into a single tasting menu experience.

Ultimately, Chef’s Table transcended being a mere food program to become a pioneering case for the business model of food IP in the streaming era. The distribution scale of 165-country simultaneous streaming provided infrastructure capable of transforming local chefs into global brands overnight, creating multi-layered ripple effects across individual chefs, restaurants, cities, and national brands.

— Fine Dining Lovers (Apr. 2025), Fast Company (Feb. 2019)

2-2. The Global Food Content Ecosystem Created by Streaming

Following Chef’s Table, Netflix cultivated food content as a core pillar of its unscripted portfolio. Street Food: Asia (2019) introduced street food vendors from nine Asian cities to global audiences—from Bangkok’s Michelin-starred street chef Jay Fai to Seoul’s Gwangjang Market knife-cut noodles and mung bean pancakes—proving the formula that “local street food = global viewing experience.”

Somebody Feed Phil has continued through Season 8 (2025), expanding to Amsterdam, Basque Country, Sydney, Manila, and Guatemala, becoming one of Netflix’s longest-running food-travel series. New formats like Dinner Time Live with David Chang and Next Gen Chef have joined the lineup, expanding the food content ecosystem across genres and geographies.

Netflix’s expanding food content ecosystem — from documentaries to live cooking shows

The key lies in the structural changes streaming platforms have brought:

First, simultaneous global release means local programs instantly become global content. For example, Korea’s Culinary Class Wars debuted on Netflix in 2024 and by its second season captured the No. 1 spot in Netflix’s global non-English TV category in its first week, ranking No. 1 in Korea, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Taiwan, with Top 10 placements across the Middle East and Southeast Asia.

Second, algorithmic recommendations lower cultural barriers and create a “content-commerce flywheel.” Netflix recommends Culinary Class Wars or Street Food: Asia’s Seoul episode to viewers who’ve watched Korean mukbang or local market documentaries. On YouTube and TikTok, the same viewers are automatically served Korean ramyeon, kimchi, and tteokbokki recipes alongside K-Food brand advertisements—forming a closed loop from viewing to recipe searching, grocery purchasing, and travel destination selection.

Third, as series survival is determined by global viewing data, new growth paths open for local production companies. When a Korean-produced format like Culinary Class Wars ranks at the top of global non-English charts, that data becomes the basis for Season 2 and 3 renewals, spin-offs, and format export potential.

— Netflix Tudum (Aug. 2025), IMDb (Jul. 2025), Fast Company (Feb. 2019)

2-3. Latest Trends in Global Food Programming

Four distinct trends are emerging in the global food programming market for 2025–2026. These go beyond format fads to signal how food IP is expanding into talent discovery, live production, local branding, and retail.

Next Gen Chef — the rise of next-generation chef discovery formats

First: The rise of “next-generation chef discovery” formats. Netflix’s Next Gen Chef (2025) uses the entire campus of the Culinary Institute of America (CIA) as its stage, where 21 chefs under 30 compete for a $500,000 prize. LeBron James and Maverick Carter serve as executive producers, connecting sports star fandom with food IP. The cast includes Michelin restaurant sous chefs and head chefs already in their 20s—positioning culinary competitions as platforms for “discovering and branding the next generation of leaders.”

Second: Experimentation with “live, real-time cooking” is gaining momentum. David Chang’s Dinner Time Live with David Chang Season 3 (2025–2026) starts from the declaration that “99% of TV and social media cooking shows are lies,” minimizing pre-prepared recipes, plate swaps, and CG corrections to experiment with real-time cooking formats.

Dinner Time Live with David Chang — the real-time cooking revolution

From a downtown LA kitchen studio, celebrity guests are invited to create impromptu dishes, filmed and edited live with minimal post-production. This hybrid format, combining live show capabilities with real-time interaction (chat and social feedback), has significant potential for future commerce integration and real-time ordering.

Third: “Globalization of local food” remains the most powerful growth driver. Netflix’s Street Food series has expanded from Asia to Latin America and USA editions, connecting Bangkok’s Jay Fai, Osaka takoyaki, Mexico City tacos, and Texas barbecue to global audiences. Chef’s Table has spawned specialized spin-offs—Pizza, Barbecue, Noodles, and Legends—moving from single-country, single-restaurant narratives to formats that “go deep into one genre or category.”

Fourth: The strengthening of K-food content’s global leadership. Korea’s Culinary Class Wars has achieved two consecutive years of No. 1 ranking on Netflix’s global non-English TV chart—an unprecedented K-food survival IP. Season 2 recorded 10.2 million views within two weeks of release, claiming the top spot for two consecutive weeks.

— Netflix Tudum (Aug. 2025), What’s on Netflix (Sep. 2025), The Takeout (Nov. 2025), Yonhap News (Jan. 16, 2026)

[Table 1] Major Global Food Content Programs in the Streaming Era

Sources: Netflix, Fine Dining Lovers (Apr. 2025), What’s on Netflix (Sep. 2025), K-EnterTech Hub compilation

PART 3

The Global Rise of K-Food Content

3-1. Mukbang: Korea’s First Food Content Format Exported to the World

Born around 2010 on AfreecaTV, Mukbang (“eating broadcast”) is the first uniquely Korean food content format exported to the world. Registered in the Oxford English Dictionary as “Mukbang” in 2021 and named Collins Dictionary’s Word of the Year in 2020, this format emerged from Korea’s rise in single-person households and “hon-bap” (eating alone) culture, filling the social void of solitary dining with virtual companionship.

Global mukbang creators on YouTube, Twitch, and TikTok exposed Korean ramyeon, chicken, and tteokbokki to worldwide audiences, serving as an indirect marketing channel for K-Food demand creation.

— Wikipedia “Mukbang,” Oxford English Dictionary (2021 entry), Collins Dictionary (2020 Word of the Year)

3-2. Chef & My Fridge and Korean Food Battle: The Dawn of the “Cheftainer” Era

The mid-2010s saw a culinary entertainment boom in Korean broadcasting. While Olive TV’s MasterChef Korea (2012–) and tvN’s Korean Food Battle (2013–2018) made their mark, JTBC’s Chef & My Fridge (2014–2019; Season 2: 2024–) had the greatest cultural impact.

Each episode’s format—completing a dish in 15 minutes using only ingredients from a guest’s refrigerator—created the entirely new category of culinary “variety show.” Chefs like Choi Hyun-seok, Lee Yeon-bok, and Sam Kim became “Cheftainers” (chef + entertainer), forming the human capital that would fuel Korean food entertainment. Many later appeared in Culinary Class Wars, continuing the lineage of K-food content.

— Namuwiki “Chef & My Fridge,” Ilyo Shinmun (Nov. 25, 2024), Harper’s Bazaar Korea (Oct. 2024), E-Today (Oct. 2, 2024)

3-3. Culinary Class Wars: The Game-Changer of Streaming-Era K-Food Content

Culinary Class Wars, released on Netflix in September 2024, is the most dramatic case of a streaming platform globalizing local food content. Season 1 claimed the No. 1 spot in Netflix’s global Top 10 non-English category from its first week, marking the first time a Korean variety show held global No. 1 for three consecutive weeks. It ranked in the Top 10 across 28 countries and recorded 4.9 million weekly views.

Season 2, released in December 2025, again achieved global No. 1, remaining on the global chart for five consecutive weeks according to the AP.

Culinary Class Wars Season 2 — achieving global No. 1 on Netflix for the second consecutive year

— Netflix Global Top 10 (Sep. 2024–Jan. 2026), AP (Feb. 13, 2026), Electronic Times (Sep. 27, 2024)

On January 16, 2026, Netflix officially confirmed Season 3 production. Unlike the previous individual competition format, Season 3 will feature a “restaurant battle” format with four-person teams, with PD Kim Eun-ji and writer Mo Eun-seol of Studio Slam returning. This represents unprecedented format innovation in global culinary survival shows. The show also won the Grand Prize in the TV category at the 61st Baeksang Arts Awards (a first for a variety show) and the Best Program Award at the 4th Blue Dragon Series Awards.

— Yonhap News (Jan. 16, 2026), Herald Economy (Jan. 16, 2026), Money Today (Jan. 16, 2026)

3-4. How Culinary Class Wars Transformed Korea’s Fine Dining Market

The Associated Press reported on February 13, 2026 that Culinary Class Wars has transformed South Korea’s entire fine dining market.

Chef Jun Lee of Seoul restaurant SOIGNÉ, who appeared in Season 2, told AP: “Before, explaining what fine dining was used to be the job. Now customers’ questions have changed. They ask about flavor combinations, cooking techniques, and philosophy.”

— AP, interview with Chef Jun Lee (SOIGNÉ) (Feb. 13, 2026)

Tei Yong, CEO of CATCHTABLE, Korea’s largest restaurant reservation platform, told AP: “I never imagined a single TV program could generate this much interest in gastronomy.” After Season 1, a Seoul-organized fine dining pop-up received approximately 450,000 reservation attempts for 150 seats (roughly 3,000:1 competition). In the five weeks following the Season 2 premiere, participating restaurants saw average reservation and waitlist registrations increase by approximately 303%.

— AP, interview with Tei Yong, CEO of CATCHTABLE (Feb. 13, 2026)

Chef Jun Lee also spoke about the essence of Korean food culture: “If you make a dish with kimchi and say it’s inspired by Korean food, is that Korean food? Korean food culture isn’t specific recipes—it’s the accumulated living habits people have built.” Regarding his signature dish “Hanwoo and Banchans,” he explained: “In English, if you call them side dishes, they sound optional. But in Korean culture, a meal without banchan is incomplete.”

Professor Jihyung Andrew Kim of Hanyang Women’s University analyzed: “Cultural content like Netflix and BTS has accelerated the globalization of Korean food.”

— AP, interviews with Jun Lee and Jihyung Andrew Kim (Feb. 13, 2026)

3-5. K-Food Exports: When Content Moves the Real Economy

According to the Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs, K-Food exports in 2025 reached a record $13.62 billion (up 5.1% year-on-year). Agri-food exports surpassed $10 billion for the first time ($10.41 billion). Ramyeon became the first single product category to exceed $1.5 billion ($1.52 billion, up 21.9%). The U.S. market reached $1.8 billion (up 13.2%), solidifying its position as the No. 1 export market. Overseas K-food restaurant outlets totaled 4,644 (up 24.8% from 2020), with U.S. outlets more than doubling from 528 to 1,106. The government targets $21 billion by 2030, positioning K-Food as a strategic industry.

— Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs press release (Jan. 13, 2026); MAFRA/aT Overseas Restaurant Survey (Feb. 6, 2025)

[Table 2] K-Food Export Performance Trends

Sources: MAFRA (Jan. 13, 2026), MAFRA/aT (Feb. 6, 2025) (*vs. 2020)

[Table 3] Culinary Class Wars: Key Achievements

Sources: AP (Feb. 13, 2026), Netflix Top 10, Yonhap News (Jan. 16, 2026), Herald Economy (Jan. 16, 2026)

[Table 4] U.S. vs. Korean Food Content Evolution: A Comparative Timeline

Sources: WSJ (Feb. 12, 2026), AP (Feb. 13, 2026), Netflix Top 10, MAFRA, K-EnterTech Hub compilation

PART 4

Five Strategic Implications for K-Content Strategy

1. Format Innovation Creates Markets

Chef’s Table created a market with its “chef profile documentary” format; Culinary Class Wars did the same with “competition + class + blind tasting”; Next Gen Chef with “next-generation chef discovery.” Season 3’s “restaurant battle” format represents yet another innovation. K-Food content must also experiment with FAST channel-dedicated programming, ASMR-travel-variety hybrids, and other new forms.

2. Streaming Platforms Are the Engine of Local Content’s Globalization

Just as Chef’s Table made local chefs global brands through 165-country simultaneous release, Culinary Class Wars leveraged Netflix to reach the Top 10 in 28 countries in its first week—a feat impossible through JTBC or tvN alone. K-Food content’s global strategy must be optimized for OTT platforms.

3. Content Creates Fine Dining Markets: The “Cultural Diplomacy” Effect

The CATCHTABLE data reported by AP—303% reservation increase, 450,000 reservation attempts—is evidence that content moves the real economy. Like Chef Jun Lee’s banchan philosophy, communicating Korean food’s unique cultural context to global audiences is the key differentiator. MAFRA’s expansion plans—12 annual OTT PPL placements and 17 Korean food sections on overseas online malls—must be systematically executed.

4. Nurturing K-Food Social Media Creators Is Urgent

Just as Mukbang became a self-generating global phenomenon, and as the Cheftainers cultivated by Chef & My Fridge continued into Culinary Class Wars, the SNS dining-sharing culture of people in their 20s and 30s—as highlighted by Professor Jihyung Andrew Kim—must be leveraged as a new channel for K-Content expansion. The “real-time cooking” trend pioneered by Dinner Time Live is also worth studying.

5. Localization Strategies Must Become More Sophisticated

According to Euromonitor’s K-Wave Index, Southeast Asia and Western Europe require completely different approaches. With the U.S. now the largest K-food market (1,106 outlets, $1.8 billion in exports), maintaining K-Food’s cultural identity—as Chef Jun Lee does by using the Korean word “banchan” as-is—is the source of long-term competitiveness.

Conclusion: The New Era of Food Content Created by Streaming

Julia Child transformed America’s dining table. Chef’s Table made local chefs into stars across 165 countries. Culinary Class Wars elevated K-food content to global No. 1. The emergence of streaming platforms has been the most decisive turning point in the history of food content—because it created an era where local programs become global content, and content moves the real economy.

The 450,000 reservation attempts on CATCHTABLE, 303% reservation increases, K-Food’s $13.62 billion in exports, and ramyeon’s $1.52 billion breakthrough are the most vivid proof of this new era. On the path toward the $21 billion target by 2030, K-Food is no longer a side effect of the Korean Wave but is evolving into a comprehensive industrial export model operating atop the global streaming ecosystem.

SOURCES

① The Wall Street Journal, “From Julia Child to ‘Tin Fish Date Night’: How Cooking Became Entertainment” (Akiko Matsuda, Feb. 12, 2026)

② Associated Press, “Netflix’s ‘Culinary Class Wars’ has transformed South Korea’s fine dining scene” (Juwon Park, Feb. 13, 2026)

③ Fine Dining Lovers, “Chef’s Table at 10: How the Netflix Series Changed Food Storytelling” (Apr. 14, 2025)

④ Fast Company, “Meet the executives who have made Netflix food TV” (Feb. 25, 2019)

⑤ Netflix Global Top 10 Website (Sep. 2024–Jan. 2026)

⑥ Netflix Tudum, “16 Best Cooking Shows and Food Documentaries on Netflix” (Aug. 12, 2025)

⑦ Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs, “K-Food+ Surpasses Record $13.62 Billion in 2025 Exports” press release (Jan. 13, 2026)

⑧ MAFRA, “K-Food+ Export Expansion Strategy” (Feb. 18, 2025)

⑨ MAFRA/Korea Agro-Fisheries & Food Trade Corporation (aT), “2025 Overseas Restaurant Industry Survey” (Feb. 6, 2025)

⑩ MAFRA, “Global K-Food Export Expansion Strategy” (Dec. 2025, inter-ministerial)

⑪ Euromonitor International, “Future Growth Potential of K-Food from a Local Perspective” (Nov. 2024)

⑫ Yonhap News (Jan. 16, 2026), Herald Economy (Jan. 16, 2026), Money Today (Jan. 16, 2026), Electronic Times (Sep. 27, 2024), Digital Daily (Oct. 9, 2024), Ilyo Shinmun (Nov. 25, 2024), Harper’s Bazaar Korea (Oct. 2024), E-Today (Oct. 2, 2024), Kookmin Ilbo (Dec. 25, 2025), Food & Hospitality Management (Jan. 2026), KED Global (Dec. 25, 2025), and other domestic and international media

⑬ Wikipedia “Culinary Class Wars,” “Mukbang”; Namuwiki “Chef & My Fridge,” “Culinary Class Wars Season 2” entries

![[보고서]전통 언론사의 크리에이터 전략 대전환](https://cdn.media.bluedot.so/bluedot.kentertechhub/2026/02/0nwc9z_202602100212.png)